Somebody at a political discussion meeting made a throwaway remark that he thought grammar schools/private schools were A Good Thing because they "increase competition".

Ho hum. At the school level, of course they do. There is no doubt in my mind that children who attend private schools get better academic results than if they'd attended state schools, which is hardly surprising, but I'm not sure that's relevant. Let's assume that state schools see themselves as competing with private schools, so maybe at the margin, they up their game slightly, again, A Good Thing.

But the point of secondary education is to equip children for a life of work and/or give them the best chance of getting a university place, which in turn is to help children end up in the best possible job. Education (beyond a certain basic level) is not really an end in itself - consider a family with children who are planning to move abroad in a few years, there is no point in the taxpayer paying for the children's education as they will not see any benefit.

Beyond a certain level, this is just an arms race. If every child were 10% better educated, then that would just mean that most of them end up in jobs for which they are 10% over-qualified i.e. from the point of view of an individual child, you want the best education you can get, taking society as a whole it would be a waste of resources.

"Competition" can mean different things:

i. If Producer A does his best to supply goods and services which are better/cheaper/whatever than Producer B, that is good for the economy, because Producer B then has to play catch up and overall standards increase. That's a clear win. Key to this is that consumers (or potential employees) have full knowledge about the goods and services (or working conditions) and can make fair comparisons (which they clearly don't).

ii. If Producers A and B have innovated and improved as much as they can, they "compete" by spending more money on advertising (providing misinformation or irrelevant facts) and trying to lock each other out by fair means or foul. That is a waste of resources and a loss.

iii. There are some competitions that are just competitions for the sake of competition, like athletics. How does society benefit if an Olympic runner sets a new world record a couple of milliseconds quicker or a few inches higher/further? Answer: not at all, at best it has a short-lived entertainment value. This is a humungous waste of resources. Compare this with films or music - that is also pure entertainment value, but people can enjoy the same films or songs for decades after they were released. Who sits down and re-watches the Olympics of a few years ago, or a horse race that was on last week? I guess nobody.

To return to the theme of private schools, you can give your child an advantage in later life by sending them there. Does that increase 'competition' in the positive sense mentioned at i. above? No, it just means that some other child is at a slight relative disadvantage for no particular reason, which is like the bad competition at ii.

To tie this in with iii., if real life were a closed system liked athletics, private school children have a one second advantage when qualifying for the Olympic running team, so they are more likely to get in. Does that mean the Olympic running team will be any better when it gets to the Olympics? Probably not, it just means that the private school kids starting training earlier, they still have a couple of years further training before the Olympics, by which time the state school kids with a one-second handicap would have caught up anyway.

Here endeth today's rant.

I'm not sure what the answer is, but it is not as simple as people think. Going to the other extreme and banning private schools might just make things worse, as there'd be nothing for state schools to compete with, so standards might slip for everybody.

Maybe the least bad system is bottom-up privatisation of state education i.e. giving parents 'education vouchers' and letting them choose which school to 'spend' them at? But if parents can 'spend' the vouchers at private schools and pay top up fees, that just compounds the original problem, so it's not as simple as that either.

Monday, 31 December 2018

Do private schools increase competition?

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

12:23

21

comments

![]()

Labels: competition, Education

Sunday, 30 December 2018

Calculating the surface area of a two and half sided regular polygon

Part 2 of this post. I struggled for a day over this.

First, write down what you know...

1. Any regular polygon can be split up into equal isosceles triangles, one for each side. The angle in the middle is 360 divided by number of sides and the other two are just (180 deg minus the middle angle) divided by 2. The area of a triangle = height (known as apothem is this context) x base ÷ 2. Times that by the number of sides, and that's the total surface area.

Worked example with a square with side length 10:

Divide the square into four triangles, the angle in the middle is 90 deg and the other two angles are 45 deg. (45 deg is also half the inside angle of the corner of a square).

Each triangle has base length 10 and height/apothem 5, area = 5 × 10 ÷ 2 = 25.

25 × 4 side-triangles = 100.

2. According to the internet, "The area of any regular polygon is given by the formula: Area = (a x p)/2, where a is the length of the apothem (the line joining the half way point of a side and the centre) and p is the perimeter of the polygon", which is saying the same thing.

3. A two and a half sided regular polygon can divided into two and a half side-triangles with an angle in the middle of 144 deg (360/2.5). The corner angles are ((n-2)*180/n) = 36, so these triangles have half that = 18 deg. Check: 144 + 18 + 18 = 180, so far so good. Using cosines and tangents and a side length of 10, the height/apothem of each triangle is 1.625, so the area of each triangle is 1.625 x 10/2 = 8.125. It has two and a half sides, so the total area = 20.3125.

4. The surface area of a three-sided regular polygon (= an equilateral triangle) with side length 10 is 43.3, and the surface area of a regular two sided polygon (= a straight line) is zero, so 20.3125 looks about right to me.

"What's so difficult about that?" asks the crowd. Nothing in itself, it took me ten minutes, but...

5. A regular five pointed star (which appears to have the same shape as a two and a half sided regular polygon, see previous post) with side length 10 has surface area of 31.027 (handy calculator here). The area of the mini-pentagon in the middle is 9.59 (using this and this).

How do I reconcile 20.3125 with 31.027?

7. If we do the calculation in 3 but using five x side-triangles (because it appears to have five sides, even though we 'know' it doesn't), that means area 5 x 8.125 minus 9.59 (to subtract the overlaps) = 31.035, pretty close to 31.027 shown above (not sure why there's a small difference).

8. Or we start with 20.3125 and assume that the two and a half sided regular polygon has no pentagon in the middle (because it has no real corners), 20.3125 plus 9.59 = 29.9, which is even further from 31.027.

Hmm. Which explanation is more likely, 7 or 8? Or neither? Is it perhaps the case that the two and a half sided regular polygon is not 2-dimensional so can't be done using normal geometry, and if so, does it have more or fewer dimensions?

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

14:44

2

comments

![]()

Labels: Maths

Saturday, 29 December 2018

A regular polygon with two and a half sides

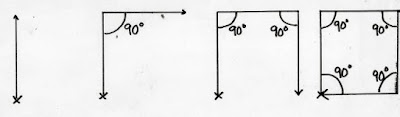

You calculate the interior angle in degrees using the formula ((N-2) x 180)/N.

For a four sided regular polygon (spoiler alert: a square) has an interior angle in degrees of ((4-2) x 180)/4 = 90. So you draw a four sided regular polygon by going a certain distance, turning right to make a corner with a 90 deg interior angle and going the same distance again, repeat until you get back to the starting point X:

That's easy enough, you can do the same for three sides, or five or six or anything until you approach a circle.

But this is maths and N can be any number you like. So let's try two and a half sides.

Interior angle in degrees = ((2.5 - 2) x 180)/2.5 = 36

Let's repeat the process, draw a line, turn right so the interior angle is 36 degrees and draw another line, then keep going until you get back to your starting point:

That is not a 'pentagram', it is a regular polygon with two and a half sides.

It is important to note that the edges do not actually touch each other where they appear to cross, those are not real corners, it just seems that way if you reduce this shape to a two-dimensional representation.

-----------------------------------------

There is a formula for calculating the number of diagonals, which is (N x (N-3))/2.

So a square has (4 x (4-3))/2 = 2 diagonals.

And a two and a half sided one should have (2.5 x (2.5-3))/2 = negative 0.625 diagonals i.e. none.

------------------------------------------

Calculating the surface area is a bit trickier, see part 2.

-----------------------------------------

You can also have a regular polygon with three-quarters of a side.

Interior angle in degrees = ((0.75 - 2) x 180)/0.75 = 300. What you end up with looks like an equilateral triangle, but the area of the polygon is everything outside the triangle, not inside it.

(You get a similar looking result if you try N = -3, an equilateral triangle in the middle that is outside the shape, and everything outside it is the polygon, but the surface area is the negative of the area outside. Can things have a negative area? Probably not, but no more than they can have a negative number of sides.)

Sadly, this doesn't work very well with other fractions, if N is 1/3 or 1/2, the interior angle is a multiple of 180 degrees, so it is just a straight line going there and back.

If N is 2/3, the interior angle is 360 degrees, so it's just a straight line going on forever and you never get back to the starting point.

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

13:58

2

comments

![]()

Labels: Maths

Friday, 28 December 2018

Help to Buy Pay Dividends

George Osborne introduced 'Help to Buy' in March 2013.

Here are the changes in dividends per share paid 2013 (or 2014 if I can't find 2013) vs dividend per share paid 2018 by the UK's biggest 'home builders'.

Barratts: 5.7p - 26.5p

Bellway: 37p - 227.5p

Berkeley (earnings per share): 221.8p - 562.7p

Bovis: 21.5p - 98.5p

Crest Nicholson: 10.6p - 33p

Persimmon: 65p - 110p

Redrow: 3p - 28p

Galliford Try: 53p - 77p

Taylor Wimpey: 0.6p - 4.8p

Telford Homes: 4.8p - 17p

Enough said?

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

11:47

7

comments

![]()

Labels: Construction, Corruption, Help to Buy

Thursday, 27 December 2018

Read it and weep.

Email from HR. The list of 'don'ts' is so long, it would probably have been quicker telling us what people are allowed to do:

The festive season is here and I am sure you are all getting excited about the Christmas party. Like any great event, it takes great people but as it is nearing the end of the year you may need to refresh yourself on some of our policies.

Please do check our company handbook to confirm our expected standards of behaviour, particularly our policies on harassment, discrimination, health and safety and conduct. All of these policies apply to you at the party and any other work social event, any breach could lead to disciplinary action.

No one guilty of these actions is likely to end up on Santa's nice list, so please act in the way you wish to be treated by your colleagues.

Aside from our policies we have a few pointers we would like you to observe. These pointers are not only to protect [employer] and its reputation but also YOU! We want to ensure you are all safe and everyone feels welcome, therefore please read and abide by them this festive season:

- ENJOY the Christmas party but don't ruin it for anybody else, drink sensibly and be aware of your behaviour. Remember your fellow party-goers are your colleagues with whom you have a duty to behave reasonably.

- During and after the party, stay with other people, don't put yourself in the position of being a little 'worse for wear' and alone.

- Make sure you know how you are getting home, book your transport in advance where required, don't allow yourself to get stranded.

- Be mindful and look after colleagues, if you feel they have had too much 'merriment' do look after them.

- Do not be let loose on Social Media, especially when commenting, 'tagging in' colleagues, sharing photo's etc.

- Think of others and do not make any comments that can be deemed to be abusive, discriminatory, or offensive.

- The Christmas party is on a weekday night therefore unless you have agreed leave for the following day you are expected to be in work (or exams) at the usual time the next morning. Be aware of your ability to drive the following morning, please drink responsibly and remember your obligations for the following day.

- And one final tip - you will be surrounded colleagues, be mindful of what you and say and do, to prevent causing offence to them or embarrassment for yourself.

These pointers are also applicable for any client parties/ socials you may be attending - don't forget you are representing [employer] at these events!

We trust everyone will accept this communication in the right spirit by appreciating that the Company is committed to meet its legal and moral obligations of ensuring your safety and wellbeing, not only in the work place but at work related functions also. None of the above should prevent us from having a great evening.

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

15:48

5

comments

![]()

Sunday, 23 December 2018

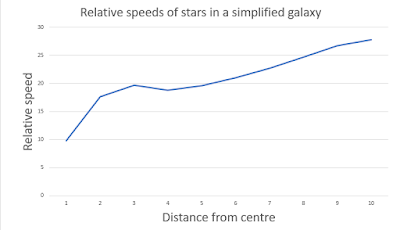

Expected and observed galactic rotation curves

Interesting article from Forbes ("Rotating Galaxies Could Prove Dark Matter Wrong") which includes the following graphic:

You can't argue with facts. The observed speeds are the observed speeds. The big mistake appears to be the other line for "Expected from visible disk".

What I don't get is why anybody would expect that in the first place. While the centres of galaxies are a lot denser than the outer bits, overall the matter is pretty evenly spread out (let's assume that the concentration of non-light emitting clouds of gas and dust are distributed in the same way as the visible stars).

Remember that a star at the outer edge of a galaxy only feels the pull of gravity inwards, but for a star further in, some of the inwards pull is cancelled out by the outwards pull of the stars further out.

Similarly, gravity from mass 'ahead' of the star, pulling it forwards is also cancelled out by gravity from mass 'behind' the star pulling it backwards. It is only the net inwards pull that matters.

In our Solar System, the Sun is 99.9% of the mass and thus causes 99.9% of the gravity and explains 99.9% of the orbits and speeds of the planets, but at a local level, the mass of a planet dictates the orbits of its moons. Earth is tiny compared to the sun, but a lot closer to the Moon. If you are calculating the orbit of the Moon, you first consider its orbit round Earth and then adjust that a bit for the influence of the Sun.

In the same way, the outer stars are orbiting round/in between/past each other as much as round the centre.

I did a spreadsheet for an idealised galaxy with

a) 11% of total matter in a circle with a radius of 2 "units" (multiples of 5,000 light years, let's say) from the centre and

b) the rest evenly spread out,

and calculated the relative net inward pull of gravity on a star orbiting 1, 2, 3 etc "units" from the centre.

The speed required to stay in a particular orbit is proportional to the force of gravity acting on it; there is no need to ponder whether a star's orbit dictates its speed; or whether its speed dictates its orbit; or a bit of both.

My spreadsheet produces a chart which shows that having made these assumptions, the relative force of gravity on a star travelling perpendicular to the centre at various distances along the radius matches up pretty well with the observations (the vertical axis units are not any absolute value, it's just relative to each other):

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

14:43

16

comments

![]()

Yet another example of how terrible Universal Credit is...

... it even fails on its own terms.

From the BBC:

The Universal Credit system leaves too many UK claimants with children facing a stark choice between turning down jobs or getting into debt, MPs warn.

The Work and Pensions Select Committee says the way parents have to pay for childcare up front, then claim it back afterwards is a "barrier to work"...

"Universal Credit claimants must pay for childcare up front and claim reimbursement from the department after the childcare has been provided. This can leave households waiting weeks or even months to be paid back.

"Many of those households will be in precarious financial positions which Universal Credit could exacerbate: if, for example, they have fallen into debt or rent arrears while awaiting Universal Credit payments. Too many will face a stark choice: turn down a job offer, or get themselves into debt in order to pay for childcare."

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

13:09

4

comments

![]()

Labels: Universal credit

Saturday, 22 December 2018

Clever definition of "land" in economic terms

One KLN (Killer Argument Against LVT, Not) which I have heard too many times is that 'land' (in the physical sense) is 'not so important any more in a modern economy'. The proponent then plucks something out of the air like intellectual property rights (copyrights, patents etc), points at a few companies who make large amounts of money from them (Facebook etc) and says that is what we should be taxing.

Clearly, in financial terms, this is nonsense, IP is in distant second place. Facebook's world wide profits are $16 billion (about $3 per user), so even if everybody in the UK is on Facebook and generates $3 profit, that's about £150 million a year. Compare that with the total site-only rental value of UK land, which is about £250,000 million a year. That's not physical land value (undeterminable) but location value (easy to measure and can only arise if the government provides 'public services').

Under general Georgist principles, government protection of copyrights and patents should either be watered down OR if we decide that it is desirable, the extra profits accruing to the rights holders should be taxed at higher rates (they ought to pay the government for enforcing and upholding these rights). This goes without saying and shows that the proponents of the KLN really haven't done any homework whatsoever.

Under general Georgist principles, there are other things that are good sources of taxation, be it oil and minerals; exclusive right to use certain radio frequencies; personal number plates; taxi driver permits, it is a very long list.

What do all the things on the list have in common?

They are all things which have no cost of production, where supply is limited (whether by nature or by the government), and quantity cannot be increased by the productive sector.

You can work hard and make a car or a table or a CD player and sell it, so those aren't 'land'. But however hard you work,

- you cannot increase the surface area of the earth at a particular location*;

- you cannot print and sell Harry Potter without JK Rowling and her publisher's permission;

- the amount of oil and minerals under the earth is a fixed (albeit unknown) amount.

- you cannot increase the width of the radio spectrum;

- you can get a physical number plate made for less than £10, but you can't choose which letters and digits are on it (so you can't just make a load of 'A1' number plates and sell them for £10,000 each);

- the council can restrict the number of people allowed to drive taxis/mini-cabs in their area.

And all these things wouldn't have value if supply were not restricted and if governments didn't do what governments do. Their value bears no relation to the efforts of the owner.

- Oil and mining companies and their employees work very hard extracting the stuff, but however hard they work does not affect its value. The current world market price of oil or gold just is what it is, and might be above or below the cost of extraction from any particular well or mine.

- When the telecoms companies bid for radio spectrum, they guesstimate what end users are willing to pay for mobile services, deduct a guesstimate and their costs and the residual value is what they were prepared to bid.

- For sure, Microsoft have created some neat software, but without copyright and patent protection, they might not have bothered so it would have much lower value.

- I'm sure taxi drivers work hard, but they understand supply and demand, which is why they lobby heavily against the likes of Uber. The extra they earn because of restrictions is unearned, it is 'rent' and they rent they get is from 'land' (in the economic sense used here), the council or city could reduce their earnings by this much at the stroke of a pen.

* Don't bore me with the notion that you can create new land by chucking rocks and concrete in the sea. That does not increase the surface area at that location. This is an expensive process, and is only worth doing if location values are very high. So it's worth doing off the shore of Monaco (and within its jurisdiction), it would be ruinous to do the same exercise half a mile down the coast if you were merely creating more France.

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

11:14

7

comments

![]()

"Gritter lorry smashes into house in Helsby"

Full story at the BBC.

I've tracked down the exact house* on Google Maps (to the left of the red arrow marked 'Helsby Running Club'), and the strange thing is, the house concerned is actually on the inside of a gentle right hand bend on the A56, looking at it the way the gritter was travelling (i.e. it crossed the opposite lane first, then hit the house). Normally, cars hits the high risk houses that are at the top of a T junction or the outside of sharp bends or similar.

* From the BBC:

* From Google Maps:

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

09:23

0

comments

![]()

Labels: car hits house

Friday, 21 December 2018

Band Aid (1984) vs Band Aid 20

I'm not familiar with Band Aid II (1989) or Band Aid 30 (2014), so can't comment on those. Band Aid (1984 original) and Band Aid 20 (2014 remake) are exactly the same song, except the remake has a little rap section in the middle.

To my mind, the differences are:

1. Most of the artists who appeared on first one had quite long lasting fame, and seem to have been rewarded with longevity. Only two (George Michael and Rick Parfitt) fell in the great celebrity cull of 2016.

Most of those who appeared on the remake only had short lived musical careers. The only one who is still active and well known is Chris Martin out of Coldplay. Bono doesn't count; And & Dec and Cat Deeley are still going, but they are TV presenters, not musicians. What happened to the rest?

Anthony McPartlin (Ant & Dec)

Declan Donnelly (Ant & Dec)

Tim Wheeler (Ash)

Daniel Bedingfield

Natasha Bedingfield

Busted

Cat Deeley

Dido

Dizzee Rascal

Ms Dynamite

Skye Edwards (Morcheeba)

Estelle

Feeder

Neil Hannon (The Divine Comedy)

Justin Hawkins (The Darkness)

Jamelia

Tom Chaplin, Tim Rice-Oxley (Keane)

Beverley Knight

Lemar

Shaznay Lewis (All Saints)

Katie Melua

Róisín Murphy (Moloko)

Snow Patrol

Rachel Stevens

Robbie Williams

Joss Stone

Sugababes

The Thrills

Turin Brakes

Will Young

Russell Mael (Sparks)

Fran Healy (Travis)

2. Musically, the first one is just droning over-layered synthesiser sludge, but the drumming (Phil Collins) is glorious and uplifting all the way through. Musically, the remake is much crisper and well-defined: just piano, acoustic guitar and some nifty guitar solos, but the drumming is really pedestrian and there's a weird bit at the end where they are just bashing some cowbells and hitting sticks together. A pity we can't edit out the rap section (well meant, but jars) and the drumming from the remake and splice Phil Collins' drums in instead.

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

17:00

4

comments

![]()

Agricultural subsidies

A debate on Twitter has helped me clarify my thoughts on agricultural subsidies:

Dr Sarah Taber @SarahTaber_bww: So ... yeah. Sometimes rural land ownership is just an instrument for rich people to extort bribes from taxpayers. "Pay me or I'll ruin your water." And sometimes you just monetize it on the corn platform.

PNW Policy Wonk @PNWwonk: That's literally not how it works. I administer conservation subsidies for a living. This is all bullshit... We contract to fix existing issues on farms. We don't pay people to not release their manure lagoons into the river. We don't work in prevention. We react to existing pollution.

Me: Same thing. Bad behaviour in past = subsidies in the present. I'm all in favour of looking after environment but we have LAWS for that. We don't pay ordinary people for not dumping rubbish on the street, we FINE then for doing so.

PNW Policy Wonk: Your first sentence makes sense. It does not relate to the second sentence at all.

benjamin @benjit14: The elimination or internalisation of costs allows best market allocation of resources. This is why we have rules, regs. laws etc. Letting others pick up the tab isn't good for society or our economy. IMHO.

Wes @lord_0f_land: If the land isn’t sustainably farmable without the manure lagoons, wouldn’t it be better to just directly ban farming on the land in question instead of subsidizing?

PNW Policy Wonk: So, ban all dairies? Come on, guys. I know you guys care about land policy, but stop talking about farming if you don't know anything about it.

Me: No, don't ban all dairies. I like milk and butter and cheese. So I as a consumer should bear the full costs of production, which might include environmental protection costs paid for directly by the farmer.

PNW Policy Wonk: The reason milk has price supports (an extra layer of govt assistance) is because you can't turn a cow's milk production on or off. But you still need to pay to feed and house them. The entire industry would collapse during gluts without support.

benjamin: Cheese is sort of like stored up milk product. I'm sure they could figure all this out without the subsidy. If there is a risk of gluts, there's a futures market for that i.e. insurance.

At this stage, PNW Policy Wonk appears to have abandoned his defence of the indefensible.

He seems to have three lines of argument:

1. We should reward landowners for not breaking the law, or pay for them to rectify earlier breaches, which is clearly nonsense.

2. Farmers and consumers should not bear the full cost of responsible production methods.

We own a home, there are rules against doing certain things, like having noisy parties every night or rearing pigs in the back garden. Our neighbours benefit if we don't do those things and we benefit if our neighbours don't do those things.

We all bought our houses knowing that those are the rules, and so the rules are to our overall mutual benefit. It's the same with factories, there are rules on how they deal with the noise and waste they generate. If anybody breaks the rules, then (hopefully) the 'state' will step in and stop them.

Why does he make the assumption that - unlike homeowners and factory owners - agricultural landowners are basically allowed to do what they want in perpetuity, and that we have to pay them to behave responsibly? That would be like me having noisy parties every night and instead of the local council stopping me, they pay for my house to be fully sound insulated.

Would food prices go up without subsidies? We have a crazy situation where agricultural land owners/farmers get subsidies, but they also pay income tax (and some National Insurance). The numbers are pretty small either way and they probably net off to nothing. So it would be fiscally neutral to scrap the subsidies and just exempt farm profits and farm wages from income tax and National Insurance* - in which case, no reason to assume that food prices would go up.

* Like forestry in the UK - they get very little in the way of subsidies (compared to arable land) for simply owning a forest, but forestry profits are exempt from income tax and corporation tax (wages are still taxable as normal, go figure).

3. Then he segues effortlessly into 'gluts' and underwriting farm incomes, which is a completely different topic.

I don't know why he thinks there are sudden gluts in milk output, because there aren't. Farmers are getting better and better at breeding cows to produce more milk and getting the milk out of them, but that is a long term trend as a result of which prices are falling long term. An individual dairy farmer's output is pretty steady and predictable.

It's arable goods where farmers can only guess how much they will be able to harvest. It is uncertainty right until the end.

It could be brilliant growing weather all season and then pissing it down, frost or drought in the last few days before the harvest and the whole thing is ruined. Just as bad, the farmer harvests pretty much what he expected, but there is a glut elsewhere so prices fall.

From the point of view of the rest of the country (consumers or government), gluts are a very good thing indeed and nothing to worry about. We should be worrying about sudden shortages, not gluts.

From the point of view of farmers, this is a precarious way to live. But in the long run, it averages out, good years and bad years. And relying on the weather is a mug's game anyway, controlling growing conditions is the way to go i.e. greenhouses, poly-tunnels, hydroponics etc (like in the Netherlands or southern Spain).

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

13:58

14

comments

![]()

Monday, 17 December 2018

Fascinating

Petition mapped

A map of the votes for the 'Leave on WTO terms' on 29/03/2019

Posted by

Lola

at

10:53

17

comments

![]()

Sunday, 16 December 2018

An alternative explanation for the shape of spiral arm galaxies (part 2)

And lo, the second and final part in my mini-series on why the planets revolving a sun follow Newton's rules/General Relativity (the larger the orbit, the slower the planet) but stars revolving a galaxy do not. Beyond a certain radius, their speeds remain constant, so they can maintain the spiral arm shape.

This is a slightly different explanation to Part 1, the conclusion of which might well be completely wrong (theses are just thought experiments, because I like thinking about stuff), but if it's correct, then the two explanations complement each other.

In words: taking gravity as a given, the orbit of a planet around the sun (or of a star round a galaxy) does not determine its final speed; it is its initial arrival speed which determines its orbit. If its arrival speed is not right for its initial orbit, it will either spiral in to the centre or fly straight on and end up in another solar system (or galaxy).

So you have to skip back to how solar systems or galaxies were formed in the first place, and there's your answer, no Dark Matter required. (The fact that nobody really knows what gravity really 'is' or how gravity actually 'works' is irrelevant if we are only thinking about its effects. I don't know how computers or the Internet work, but I can still use them.)

There was basically loads of stuff whizzing round, it formed the only patterns it could possibly have formed. If you just look at finished solar systems or galaxies, you ignore all the stuff that passed a system or galaxy with which its direction and speed were not compatible and so ended up in another system or galaxy, or floating through space on its own; for a bit of a stuff to end up particular system or galaxy is the exception not the rule.

A solar system or a galaxy is the result of a series of happy coincidences. It's like evolution. To invoke Dark Matter is like invoking Intelligent Design.

With pictures:

1. A simple solar system.

Planets are formed from dust and rocks which were spewed out by dying stars and whizz through space until they are caught by the gravity of a sun. They don't arrive fully formed, but to be caught, their constituent rocks have to be travelling at the right speed and distance from the sun.

For a given distance from the sun, if Rock B is travelling too slow, it will fall into the sun, if too fast, it will change path slightly but then whizz off into space again. Its speed has to be 'just right' for it to end up in a fairly stable orbit. It then merges with other rocks travelling on a similar orbit at a similar speed form a planet. Cruithne is travelling round the Sun on a similar orbit to Earth at a similar speed, but is more or less opposite Earth so the two won't collide and merge any time soon.

Rocks and planets have no memory, when a planet reaches the place illustrated with a small white circle, travelling perpendicular to the sun (pink), all they 'know' is that they want to continue travelling in the direction of the solid arrow. It doesn't matter whether they just arrived fully formed along the solid arrow or were already in that orbit at that speed.

2. The right speed is different, depending on what their (initial) trajectory is

Imagine rock A and rock C, which happen to pass into the sun's gravity (the dotted circle), travelling at the same speed, and let's imagine that this is the optimum speed for rock A. Rock A feels a strong gravitational force as it passes quite close to the sun. So I have coloured the sun orange to denote 'strong' gravity'.

Rock C, travelling at the same speed, only feels weak gravity from the sun (coloured yellow to denote 'weak' gravity), so for that particular orbit, it was travelling too fast, so is deflected slightly but flies off into space again.

3. The optimum speed is slower, the further from the sun the rock was initially travelling.

Stands to reason. If Mercury (or the rocks which formed it) had been travelling slower, they would have spiralled in the sun. If the gas in Neptune had been travelling faster, it would have passed straight on.

4. Mass is much more evenly distributed in a galaxy than in a solar system

Newton/GR is easy with a solar system, as the sun makes up over 99% of the overall mass. You can more or less ignore the pull between the Earth and Mars when studying their orbits.

But how are galaxies formed? It's a bit more complicated than solar systems. Consensus seems to be that you start with a large gas cloud, which contracts under gravity to form the first few stars, with strong gravity, then other nearby or passing gas clouds, which might or might not have already formed stars, are caught up in it.

Picture 4 is analogous to picture 2. Whether or not stars arrive fully formed does not matter, they have no memory. When they have reached the point marked with a star and are travelling perpendicular to the centre of the galaxy they might as well have just arrived from outside (where they only experience medium gravity, coloured yellow) and in the absence of gravity 'want' to continue to travel in a straight line. So let's imagine two stars A and C which are travelling at the same speed, just different distances from the centre.

There are stars to the left and right of A's line of travel. The ones to its right cancel out the pull of gravity from some of the stars to its left. It only feels the net pull of the stars in the region coloured orange (strong gravity), yellow (medium gravity) or green (weak gravity), which adds up to a certain total gravity. Let's assume that it is travelling at the optimum speed for that distance from the centre, so falls into a stable orbit.

Now look at it from the point of view of star C, which arrives at the same speed, parallel and at the edge of the galaxy. There are no stars to its right, it only feels a pull to the left. The regions which pull it are given the same colours (strong = orange etc), and as you can clearly see, it would be reasonable to assume that it actually feels a stronger pull to the left than star A. I adapted this idea from a Dark Matter Sceptic on YouTube called Jeremy Kenny, who is probably as well qualified as I am, in other words, not at all.

So if star C is travelling at the same speed as star A, it is 'too slow' to stay in that orbit and will spiral in to the centre.

5. The 'optimum speeds' for stars in a galaxy is the other way round to planets in a solar system

Picture 5 is analogous to picture 3, which told us why inner planets have to travel faster than outer ones.

Picture 5 shows why with stars, it is the other way round - apart from the inner stars orbiting the very centre (massively heavy, loads of Black Holes and stars etc) which follow normal rules, for outer stars (more than 5,000 light years out, or whatever the cut off point is) the optimum speed to stay in orbit is the same (or faster) the further out you are.

For star A, closer to the centre, most of the galaxy's gravity cancels out, it only feels gravity from stars in the areas coloured yellow (medium gravity) or green (weak gravity). To stay in that orbit, it must be travelling slowly. Fewer stars cancel out for star B, it is pulled more strongly to the left, so it is has to be travelling as fast as or faster than star A to remain in a stable orbit; and so on for star C right at the edge.

Hope that settles matters!

----------------------------------------------

A lot of people go for the 'dark matter' explanation, for which there is only indirect evidence and absolutely no direct evidence. I am a 'dark matter sceptic' if you will, which is why the True Believers in Dark Matter (a phrase coined by Prof. Stacy McGaugh, who used to be one until he discovered MOND, his lectures are highly recommended) would deride me as a 'Gravity Denier' if they knew I existed. (Please note, Dark Matter is not to be confused with Dark Energy, something else entirely, which might be negative mass for all we know)

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

15:21

3

comments

![]()

Friday, 14 December 2018

Advent Calendars

The Mrs dutifully bought advent calendars for me and herself (the nice 'Celebrations' ones).

Every morning I want to be a rebel and open any old random window, but then I always chicken out and look for the correct one for the day. To do otherwise would just feel wrong, and not in a good way.

How daft is that?

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

15:54

10

comments

![]()

Labels: Xmas

Thursday, 13 December 2018

Questions to which the answer is no.

Via @SOLZ_ZYN, from Property 118, article reproduced in full:

Negative equity – are the banks responsible?

A few of my houses are coming to their end of term and the lenders want their money back.

They knew my exit strategy was refinance or sale, but now they don’t seem to recognise any responsibility for the negative equity.

When the banking crisis occurred it followed naturally that house prices dropped dramatically as lenders either folded (albeit bailed out by the government) or sold their book to others. (Not necessarily even lenders).

The banking crisis was caused by reckless lending and the banks ran out of money and were unable to continue their business. The bankers have apologised unreservedly for their error of judgement. Great! But now when some areas are still struggling with negative equity they should (in my opinion) extend the mortgage for a lifetime. Or if they want to recoup their capital reduce the amount owing to an amount that would enable refinancing.

The FCA do not regulate buy to let mortgages, however, the mortgage is a contract. In contract “every contract has an implied contract term that the lender will perform the contract with care and skill”. Surely lending recklessly and being unable to sustain your business, which then has the knock on effect of destroying the value of my investment, is lacking in the performance of care and skill?

There is so much more I can add to this argument but would like to hear a reasonable response that says I’m wrong. I just cannot see it any other way.

But would appreciate your comments.

Gwen

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

17:10

4

comments

![]()

Labels: Home-Owner-Ism, landlords, Nequity

Wednesday, 12 December 2018

An alternative explanation for the shape of spiral arm galaxies (part 1)

We are familiar with spiral arm galaxies. The 'problem' is that to maintain their shape, the rotational speed of the outer stars must be the same as inner stars.

That is in stark contrast to smaller systems like the solar system where the innermost planet Mercury goes round the Sun every 88 days, the rotation period gets progressively longer the further a planet is from the Sun, so the outermost planet Neptune (sorry, Pluto!) goes round every 165 years. This follows the inverse square law - see 2. below.

The still-fashionable explanation - Dark Matter - has been debunked endless times, most recently in the last few days.

Density wave theory is a contender, but the real front runner must be Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND), which just says that people get Newtonian Gravity slightly wrong.

In such cases, I find it helpful to write down everything you know and then draw the obvious conclusions.

1. The surprising similarities between behaviour of light and gravity

Yes of course, gravity doesn't really exist as an independent force, but for simplicity we might as well assume it does. The behaviour of light is well studied and understood, so let's use it as an analogy:

* The speed of light = the speed of gravity waves (I remember vividly reading about some fairly conclusive experiment/measurement in 2002 or so and thinking "Well, yes, obviously...")

* Photons = gravitons

* Light waves = gravity waves

* Ripples in electromagnetic field = ripples in space time

2. The inverse square law

The brightness of light is inversely proportional to the square of the distance. This stands to reason. The source is emitting the same number of photons every second and they travel in straight lines, so the surface ares of a hypothetical sphere with radius one light second (with its centre at the source) contains as many photons as the surface area of a sphere with radius two light seconds.

But the surface area of the two-light-second-radius sphere is four times as large (surface area of a sphere = 4 Pi r^2) as the one-light-second-radius sphere, so the light (number of photons) is only one-quarter as bright. Real life example: because of perspective, a light a certain distance away also only looks one-quarter as big as one half as far away, so if you look at a row of street lights stretching into the distance, they all appear to have similar brightness.

The same thing happens with gravity - the force of gravity you feel is also inversely proportional to the square of the distance. To continue the analogy, there are a quarter as many gravitons per unit area of the second sphere.

3. Gravity bends light waves, and...

That light waves appear to bend when they pass near massive objects is also undisputed (I hope); gravity bends light waves. Although photons have no mass so shouldn't respond to gravity. General relativity explains this.

The massive object bends light and so it changes the shape of the hypothetical sphere considered in 2. If the observer is at A, the massive object at B and the light source (star) at C, the light sphere emitted by C is stretched a bit. It is more like a boiled egg shape, with the star at the centre of the yolk and the observer at the pointy end. The observer sees brighter light than they 'should'; the star appears larger/closer than it really is; the observer receives more photons than they 'should' etc. The massive object acts like a lens.

Galaxies bend light on a much larger scale than a single massive object (h/t Dyson and Eddington in 1919), hence the term galactic lens. If the light-gravity analogy is to hold, then gravity must also bend gravity waves. I'd guessed this all along, but Googled it this morning to check and yes, they do. For sure that's 'only' a blogpost, but she's a proper qualified scientist and her post is full of links to official stuff.

UPDATE, a few days later a physicist explained in Forbes:

This tells us, unambiguously, that gravitational waves, as they travel through the Universe, are affected by the warping, curvature, and stretching of space.

There’s another piece of evidence, too. The kilonova event of 2017, where we observed the merging of two neutron stars in both gravitational waves and in electromagnetic light, had these two signals arrive nearly simultaneously: with less than a 2.0 second difference between them.

Traveling from a distance of over 100 million light years (and given that there are over 30 million seconds in a year), we can state that the speed of light and the speed of gravity are equal to within better than 1 part in a quadrillion (1015).

This tells us another important piece of the puzzle: whatever time delays take place for photons as they travel through the Universe owing to the curvature of space also occur for gravitational waves. Whenever you enter or leave an area where gravitation is strong, you have to follow the path set forth by the curvature of space. Around a massive galaxy, for example, like the one we observed the kilonova in, space is curved, and all massless particles have to climb out of that potential well.

The fact that photons and gravitational waves arrived simultaneously tell us that they had to experience the same effects as one another from the curved space they passed through.

Here's the kicker:

Every star's gravity field bends, and is bent by, the other stars' gravity fields. Start with two stars (sources of light AND sources of gravity). Each light/gravity sphere is bent egg-shaped, so we end up with a two overlapping light/gravity spheres shaped like a Rugby ball. Which is like an American football but a bit less pointy.

Add more stars and the gravity fields merge and flatten out into something the shape of an Olympic discus; add a whole galaxy and the galaxy's gravity field gets flatter and flatter.

4. Modified Newtonian Dynamics

Enter stage left, towering giant of non-bullshit astro-physics, Mordi Milgrom. What his MOND (link at start of this post) says is that up to certain radius (about 5,000 light years, 5 kly for short), the force of a galaxy's gravity on stars follow the normal Newtonian inverse square law; beyond that certain radius, the force of gravity diminishes inversely proportional to distance i.e. pull of gravity on outer stars is stronger than expected, meaning they spin round faster than expected, so have the same rotational speed as inner stars, maintaining the spiral arm shape, the problem we are trying to explain.

The problem I have when I read up on his MOND (whether he deliberately chose an acronym that spells the German word for 'moon' is unknown) is that nobody explains why there is jump from normal Newtonian gravity nearer the centre of a galaxy to MOND gravity beyond a certain radius, it all seems a bit arbitrary.

Observations fit his equations because he tweaked his equations to fit observations etc. Which is why I have had to work out (reverse engineer?) the actual explanation myself.

5. A worked example

Let's start with a star 5 kly out from the centre where Newton's rules stop applying. It is pulled towards the centre with a gravitational force of X (whatever unit that is).

* Under normal Newtonian inverse square root rules, a star 15 kly out - at the other end of a spiral arm - only feels a pull of X/9 of that (15/5 = 3, 3^2 = 9)

* MOND says a star 15 kly out feels a pull of X/3 (15/5 = 3) not X/9, which seems like a huge discrepancy.

It's not such a big discrepancy really. The star 15 kly out just 'thinks' it's only 9 kly out (as it feels the same pull as if it were only 9 kly out).

Maths: The pull of gravity towards the centre of gravity on the surface of a hypothetical perfectly shaped sphere with radius 9 kly centred on the centre of gravity is (approx) 1/3 of that on the surface of a sphere with 5 kly radius. 9/5^2 = 3.24, = 1/3.24 = close enough to 1/3 for our purposes. (The correct number is 8.56 kly but let's go with 9 kly).

Possible explanation: the 15 kly star is actually sitting on the surface of a 9 kly-radius sphere... which has been stretched out in every horizontal direction, so it has height +/- 18 kly and width of 30 kly (see 3). The star is 15 kly from the centre, but in gravity terms, it is only 9 kly from the centre.

Bonus: Newton wasn't wrong, it's just that you can't expect his inverse-square-law spheres to be perfectly spherical in all conditions. They are at the small scale of a solar system where the central Sun is somewhere between 99.8% and 99.9% of the total mass of the solar system anyway; not in a large galaxy where mass is more evenly distributed and the cumulative effects are much greater.

6. If anybody has access to the right telescope...

... and somebody else knows how to do the calculations, I'm happy to split the Nobel Prize money three ways. Get to it!

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Part 2 to follow, including diagrams and ways that we can test this theory i.e. what sort of results it predicts and how to observe and measure them.

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

23:56

11

comments

![]()

Tuesday, 11 December 2018

An alternative explanation for why Planet Earth bulges at the Equator

Easy explanation - the world is spinning round, so the equator gets thrown outwards slightly, like people spinning balls of pizza dough into flat pizza bases.

Or maybe not.

Here's my gloriously long winded explanation...

As top telly scientist Prof. Jim Al-Khalili, explained in his programme "Gravity and me":

Rule 1. There's not really such a thing as gravity. Time runs more slowly near large masses and smaller masses want to move to where time moves more slowly.

Rule 2. Time moves more slowly for fast moving objects.

So with GPS satellites, they have to make a net adjustment between two opposite effects - the clocks on the satellites seem to be running a bit faster (than clocks on earth) because they are further away from the mass of the planet; but the satellites are moving quickly, which means clocks on satellites seem to be running a bit slower (than clocks on earth). The two effects don't quite cancel out.

The prof realised (after some false starts to which he cheerfully 'fesses up) that the same applies if you compare a clock at the North Pole (nearer centre of earth but not rotating) with a clock at the equator (further away from centre of earth but moving at 1,000 mph). And - unlike for satellites - these two effects exactly cancel out!

This is hardly surprising, really.

If we consider the earth to be a large blob of slow moving liquid (and ignore the thin layer of rocks floating on top), it must be clear that if a drop anywhere on the surface of the blob can move to somewhere where time is passing more slowly, it will do so. (This is no different to considering a liquid that has been poured onto a flat surface). So we can safely assume that four billion years later, the clocks for all drops on the surface of the liquid part of earth are moving at the same speed.

That is ultimately why the earth bulges at the equator - if you started with a perfect sphere, a clock at the equator would run more slowly than a clock at the North Pole (same distance from the centre of the earth and moving quickly).

So liquid on the surface flows from the Poles towards the equator until the equilibrium is reached, where the extra radius means a clock on the surface at the equator is a little bit further from the centre of the earth, which speeds up the clock a bit. The clock at the North Pole is a little bit nearer the centre, so slows down a bit, and both clocks (in fact all clocks anywhere on the surface) are running at same speed.

All part of the service!

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

13:56

13

comments

![]()

Monday, 10 December 2018

Teresa May - Reader Poll

1. Trying to wreck Brexit?

2. Completely f*****g useless?

3. Just stupid?

4. Is absolutely lovely and fragrant and trying to do the Best for Britain?

Posted by

Lola

at

17:52

6

comments

![]()

Labels: Brexit, FOP, Theresa May MP

Sunday, 9 December 2018

Absolute and relative values

Example One - Ted Heath. Having stoked the house price bubble in the early 1970s (the top of an eighteen year cycle), UK governments then had to spend five years deflating the house price bubble, but to avoid people noticing so much, what they did was create massive wage and price inflation; the correspondingly high interest rates kept house prices at the same absolute nominal level, but after five years wages (and all other prices) had doubled, so in relative terms, house prices had halved.

(Let's not get bogged down in precise dates and amounts, it is the principle that matters.)

--------

Example Two - people say a weakness of the Council Tax system is that it is based on 1991 values; in some areas nominal house prices have 'only' increased threefold since then, in others they have increased tenfold. Which leads people to say that there should be a revaluation.

As a matter of fact, because of the way the Council Tax system operates mathematically, a full revaluation to 2018 values would make little difference. This is because each local council has to collect a certain arbitrary £ amount. So let's imagine an area where all homes are worth roughly the same amount (a suburb consisting of three-bed semi-detached houses). In that area, the tax per home is simply the total £ amount divided by the number of homes. It does not matter whether you use 1991 value of £80,000 each or 2018 value of £320,000 each.

Clearly, there will be less valuable and more valuable homes in any local council area, but it is only relative values that matter. So if the selling prices of all homes in an area have increased by a similar percentage since 1991, the final bills will be much the same.

--------

Example Three - some time at the start of the Tory-Lib Dem coalition in 2010, a senior Tory (I can't track down exactly which one) said that one of their goals for government was to ensure that house prices would increase slower than wages, i.e. that in relative terms, housing would become more affordable.

UPDATE: RS in the comments points out it was their Housing Minister, who at the time went under the name Grant Shapps, who "spoke of a 'rational' market in which house prices fell in real terms, by increasing by less than earnings."

--------

Example Four - I had a heated discussion with another Georgist recently (he has posting rights on this blog so is free to put his side of the argument). He said that 'we' want to keep house prices (i.e. land prices) as low as possible. For sure we do, but my point was that to placate the Homeys, we must make the point that absolute house prices would not fall if the tax shift were done properly.

If absolute house prices stay the same and disposable incomes go up (so houses are much cheaper in relative terms), then everybody's reasonably happy. It must be clear that selling prices are largely determined by credit availability i.e. banks willingness to lend and borrowers willingness to borrow i.e. borrower's ability to repay mortgages. As first time buyer disposable incomes would be significantly higher (the LVT on the homes they buy would be half as much as the reduction in taxes on their output and earnings, not to mention the boost to the economy), the tax shift can be easily be tweaked so that house prices do not fall at all.

We ended up agreeing to disagree, but I like writing things down for posterity.

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

13:57

13

comments

![]()

Labels: Maths

Friday, 7 December 2018

Dark fluid: this bit doesn't make sense

From Space Daily:

The preamble:

Our best theoretical model can only explain 5% of the universe. The remaining 95% is famously [what sort of justification is that?] made up almost entirely of invisible, unknown material dubbed dark energy and dark matter. So even though there are a billion trillion stars in the observable universe, they are actually extremely rare.

The two mysterious dark substances can only be inferred from gravitational effects. Dark matter may be an invisible material, but it exerts a gravitational force on surrounding matter that we can measure. Dark energy is a repulsive force that makes the universe expand at an accelerating rate.

The two have always been treated as separate phenomena. But my new study, published in Astronomy and Astrophysics, suggests they may both be part of the same strange concept - a single, unified "dark fluid" of negative masses.

Jolly good, now here's the logic...

Negative masses are a hypothetical form of matter that would have a type of negative gravity - repelling all other material around them. Unlike familiar positive mass matter, if a negative mass was pushed, it would accelerate towards you rather than away from you...

My model shows that the surrounding repulsive force from dark fluid can also hold a galaxy together. The gravity from the positive mass galaxy attracts negative masses from all directions, and as the negative mass fluid comes nearer to the galaxy it in turn exerts a stronger repulsive force onto the galaxy that allows it to spin at higher speeds without flying apart.

That's a poor explanation. How can positive mass attract negative mass, but negative mass repel positive mass? Either the two repel each other (being mirror images)... or the two effects would cancel each other out.

-------------------

Greater minds than mine reckon that there's no such thing as gravity anyway: space-time is bent by mass and objects travel 'downwards' to where time is passing more slowly (where there is more mass slowing time down). Just like a log which is floating down a river will come to rest in a static pool on the bank of the river if given half the chance.

So negative mass would just have the same effect on matter with negative mass. The logical conclusion would be that matter with positive mass would perceive time as passing more quickly if it were near negative mass, leading to the repulsive effect.

And what if you manage to force negative and positive mass matter together and mix it together, does it then have zero mass?

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

16:01

17

comments

![]()

Labels: Science

Clean Brexit 'Cliff Edge' Fallacy

The fallacy of the 'cliff edge' when (if?) we leave the EU without a 'deal' with it.

Evidence 1. Chat with major insurer underwriting admin. bod in Major Corporates business. They are targeting having all their contracts sorted out to accommodate EU and UK law by 1st January 2019

Evidence 2. M&G sorting out their funds https://www.mandg.co.uk/investor/articles/reminder-planned-fund-suspensions/

I just bet that all those supposedly 'fragile' supply chains will also be sorted out well in time as well.

Markets always eventually sort out the chaos caused by bureaucrats - if they are left alone to do so.

Posted by

Lola

at

11:04

7

comments

![]()

Thursday, 6 December 2018

Today's statement of the obvious

From the BBC:

Bush was almost certainly the last US president to have fought in World War II.

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

14:03

3

comments

![]()

Labels: george hw bush, History, USA

Tuesday, 4 December 2018

Killer Arguments Against LVT, Not (450)

Two equal and opposite ones:

1. Landlords will just pass on the tax to their tenants.

2. House prices will fall, people will be trapped in nequity, banks will go bankrupt, world will come to an end etc.

-------------------------------

Clearly, if 1 is true, then house prices would be unaffected, as the net income/benefit from owning one is unchanged.

So at least one of them is untrue, or the truth is somewhere in the middle. Maybe rents would go up a bit and house prices down a bit.

(Also, falling house prices would A Good Thing overall and any transitional issues could easily be smoothed out, but let's assume it's A Bad Thing.)

Having thought about it for a while, prediction 1 will, after the event *appear* to have been correct - provided there are equal and opposite cuts to VAT and National Insurance (and minor taxes like Council Tax).

Rents are set by the disposable incomes of tenants who are in work; an average tenant household would have £15,000 more disposable income, so we can assume that rents would increase to soak up half that, which (coincidentally) would cover the LVT on an average rented home.

This is neither A Good Thing nor A Bad Thing, nor is it an argument against (tenants would still end up a lot better off; landlords would not lose out).

We can therefore safely conclude that KLN 2 is quite simply not true (regardless of whether it would be A Good Thing or A Bad Thing):

a. If net rents stay the same, then the price which landlords would be willing to pay for a home would also be unaffected.

b. It's mortgage lending which is the main driver of house prices. Buyers are in a borrowing arms race and whoever is prepared to borrow the most gets the home, banks are willing to lend up to an 'affordability' pain threshold i.e. mortgage repayments should leave borrowers enough to live on plus a bit of a cushion.

Borrowers' disposable incomes, even after deducting the LVT they will be paying, will be considerably higher, so if anything, the amounts which banks would be willing to lend will go up, meaning that it is possible (but unlikely) that house prices would actually go up slightly.

c. Clearly, if most people's disposable income goes up, then some other people's income will go down, i.e. semi-retired and retired in more valuable homes. But such people are unlikely to be taking out mortgages as banks don't like repayment periods which extend into people's retirements.

Therefore, their fall in disposable income has zero influence on house prices, they will be trading down to minimise their LVT bills and free up cash i.e. the opposite of taking out a mortgage to trade up.

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

15:59

2

comments

![]()

Labels: KLN

Monday, 3 December 2018

Remainer non-logic

PaulC 156 here:

And the fact that the average polls are showing a swing toward remain does the case no harm.

More especially so as the majority of those who've died since the referendum would have been leavers and the majority of those formerly too young to vote are remainers. So the Young People get to decide. Can't be too bad can it!

It is quite true that older people were more likely to have voted Leave and younger people more likely Remain.

It is also true that a few hundred thousand of the older people who voted Leave two-and-a-half years ago have since died, and a few hundred thousand more younger people, who are more likely to vote Leave, are now eligible to vote.

So another Referendum is a slam dunk for Remain then?

What this ignores is that a few hundred thousand middle aged people who voted Remain last time will have crossed the Rubicon and would vote Leave if there were another Referendum; it all cancels out neatly.

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

14:34

28

comments

![]()

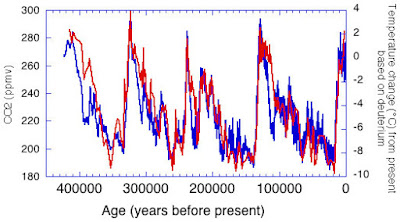

"Sir David Attenborough: Climate change our greatest threat"

From the BBC:

The naturalist Sir David Attenborough has said climate change is humanity's greatest threat in thousands of years. The broadcaster said it could lead to the collapse of civilisations and the extinction of "much of the natural world".

He's right, but for the wrong reasons.

It appears that we are teetering towards the next Ice Age (h/t paulc156). When that starts - in a few centuries or a few millennia - the outcome will be far, far worse (for mankind) than anything that the Warmenists have dreamed up:

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

13:39

18

comments

![]()

Labels: Global cooling

Sunday, 2 December 2018

With grim inevitability...

From the BBC:

If MPs don't back Theresa May's Brexit deal there could be another EU referendum, Michael Gove has said.

The leading cabinet Brexiteer said Mrs May's deal was not perfect - but if MPs did not vote it through on 11 December there was a risk of "no Brexit at all". He told the BBC's Andrew Marr show there may now be a Commons majority for another referendum.

Which is what I expected to happen all along.

Heck knows what Gove's motivation is here - on the one hand, he wants to appear loyal to May by backing her deal, his wording implies that he thinks that having another Referendum is A Bad Idea.

We know of course that a majority of MPs are Remainers who would be delighted at having the result of the previous Referendum declared null and void and having another go at Project Fear (which backfired on them so spectacularly last time).

So this is a motivation for MPs to vote against May's deal, which from May's point of view looks like a fail, but actually from her point of view it's a win (she campaigned for Remain). Assuming that Gove is still a Leaver some twisted opposite logic applies.

Posted by

Mark Wadsworth

at

15:47

15

comments

![]()

Labels: Brexit