The simplistic view is that if we allowed more houses to be built, prices would come down.

One of the fatal flaws in this theory - apart from there being no real life evidence to back it up - is the assumption that demand is fixed. It is not. High prices in e.g. London could be solved by allowing more homes to be built - but only if there were a complete freeze on migration to the capital (whether from elsewhere in the UK or elsewhere in the world).

So supply - of housing or commercial premises - creates its own demand. There are three million households in London and three million homes. If they built another million homes, another million households would move to London. By and large prices would not change. With agglomeration benefits, they would actually go up slightly, but that is another topic.

The next fatal flaw is the theory assumes that land is uniform and freely interchangeable. For sure, if there was a sudden glut of coffee (and no protectionist intervention, such as price subsidies or deliberate destruction of the excess crop), coffee prices would go down. That is because coffee is freely traded around the world and is homogeneous. A coffee bean in the UK is the same as a coffee bean in New Zealand.

But each and every plot of land is unique and a mini-monopoly in its own right. So each has its own value which cannot be influenced by the owner.

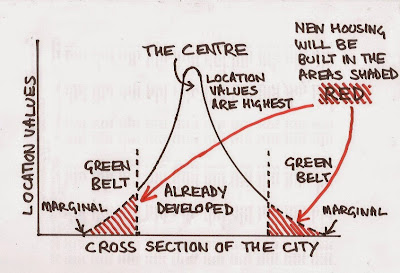

Let's draw a cross section of a typical city; land values are highest in the centre and then tail off towards the margin. In the absence of planning restrictions and the Hallowed Green Belt, builders would build all the way out to the margin where land values are virtually zero.

But the Green Belt restricts them; if they were allowed to build a bit further out, they would be building in the areas shaded red, and they would only build them if they know they can sell them; i.e. for every home they build, one new household moves to the city. Supply creates its own demand. The price of these homes (or indeed commercial buildings) would of course be lower than those nearer the centre, but the price of existing homes would not change much (and might go up).

By and large, by allowing more development in the red shaded areas in high value areas (London and South East), it would only be the price of homes in towns from which people emigrate which would fall - there would be the same number of homes but fewer households, so same supply, less demand. The effect of dis-agglomeration would push them down a bit further still, i.e. all the ambitious people have moved elsewhere (compare West with East Germany).

Inconvenient Failures

9 hours ago

17 comments:

Very few commodities are true commodities, Mark. Coffee beans are variable by variety, crop, location year, price, etc. As a coffeeholic, I am very aware of this. It's a basic economic fallacy to think tehre is a uniform substance called "bread" or "corn" or "steel" etc.

The first part is also fallacious to a degree. If you make more of a product available in one location and not another, when there is unsatisfied demand people will seek it out. But that's because of the unsatisfied demand. If people would move to London if more houses were there, it means people álready want to move to London but can't due to the lack of houses.

Additionally, the migration from, say, Liverpool, would cause Liverpool prices to fall until they become sufficiently desirable to attract buyers.

This is how all market work. Supply and prices adjust to the desires of consumers.

The key point being that supply doesn't create demand. That is a deliberate misstatement of Say's Law by Keynesians. Say said that "people produce in order to consume". A better way of saying it is that demand allows supply.

Somebody wants a chair, I'm a carpenter with a lump of wood and some tools, so I make them a chair. If I make a chair and nobody wants it, it won't "create a demand". I'm just stuck with a chair.

So a carpenter produces chairs to supply existing demand, and enable him to consume and thus demand goods from other people which are not chairs.

IB, yes I know there are different types of coffee, but they are similar enough to be interchangeable. I have no idea what beans they use for my Nescafe powder or in the cappuccino I drink most mornings in town.

"If people would move to London if more houses were there, it means people already want to move to London but can't due to the lack of houses.

Additionally, the migration from, say, Liverpool, would cause Liverpool prices to fall until they become sufficiently desirable to attract buyers."

Yes, that is exactly what I said. How do we recognise unsatisfied demand? By looking at land values. If they are above zero, then there is demand for development there.

And I also made the point that increases in supply of freely tradeable goods does not influence demand. You say chairs, I say coffee, same principle.

But your London/Liverpool point illustrates exactly that increased supply of housing in 'desirable' areas only pushes down prices in 'undesirable' areas, which again is exactly what I said.

And businesses in London benefit enormously from increases in population - more customers and available workers - so that pushes up the value of commercially used land in London (and no doubt further reduces it in Liverpool), which at the margin spills over into higher residential prices etc.

Demand isn't "created" (unless we are talking about an improvement in productivity that raises aggregate demand).

Aggregate demand is tapped into, or shifted.

So, it's not just a case of ring fencing London, but the UK, if you wanted to see a drop in HP's by building more homes. And we'd also have to ban people from moving from small towns to larger cities.

Or we could demolish our housing stock, thereby forcing people to emigrate, and reverse the effects of agglomeration. So again, rather counter intuitively, house prices would fall.

Observation tells us that the highest land values, and therefore HP's are the places with the the highest concentration of people.

Economists dismiss this Global phenomena, and say it just so happens that the biggest cities in the World have must have(no evidence supplied) the most restrictive planning regs.

Which begs the question, how did anything ever get built in the first place then?

There is one more point worth mentioning. Capitalised rents cause deadweight losses.

One of the symptoms of this is urban sprawl.

The HGB is a regulation to help mitigate this. So if we did allow unrestricted building, the mis-allocation and inefficiency we already suffer would increase.

So, I suppose there could be an argument that building on the HGB would lower aggregate HP's, but so could any number so destructive ways that lower GDP.

Let's start a war with France. That would work too. And think of all the young men we'd get off benefits!

13 July 201

BJ: "Demand isn't "created" (unless we are talking about an improvement in productivity that raises aggregate demand). Aggregate demand is tapped into, or shifted."

Yes, we have talked about this and I completely agree. For example, after Westfield Stratford opened, rents in other shopping centres in East London went down quite markedly.

However, if there are two countries with a population of ten million, and one country is big with twenty widely spaced towns of half a million each, and one is a small city state of ten million, the chances are that total land values are higher in the city state.

Since land is - to all intents and purposes - in fixed supply, MW's analysis should be self evident.

Moving this 'supply creates its own demand' meme on a bit, it has always seemed to me as a self employed bloke - admittedly with a knack of being able to always find work - that supply must come before demand. In simple terms I know that I have to produce something, and sell it, before I can go and buy something I need or want. In straightened times I adapt my offerings to suit the reduced circumstances of my customers,and keep trading.

I continue to completely fail to understand why people don't see this. Everyone worries about 'aggregate demand', but in my experience (which does not include total economic breakdown) demand is infinite. People always want stuff - products and services - and frequently don't know what stuff they want until it is shown to them (mobile 'phones?).

It's a conundrum.

Lola-

The point about Say's Law is that people supply in order to consume, as you do. You have to put something on hte market that other people want. If your produce is then purchased, you can go on to consume somebody else's.

Which is the main thing about Say's Law; you can't have aggregate oversupply or undersupply; if you can't sell your stuff, it's because you're making the wrong stuff and need to switch to making something else.

It's also worth mentioning that demand for goods and services is not infinite, it's just nowhere near saturated yet for most people. Which is why rich people run out of stuff to spend their money on and just sit on it, or start giving it away in philanthropic projects. Bill Gates's actual demand saturated several billion dollars ago.

What this means is that with sufficient economic growth we really can reach a point where everyone works less and less while wanting for nothing, because demand will have saturated. We've got quite a way to go yet.

A Georgist may argue that the one thing that this argument doesn't apply to is land, which may well be a valid argument.

IanB. This 'rich people sitting on it' bit. Yes. But. Even sitting on 'it', if 'it' is in the bank 'it' is still being used. True, if 'it' is under the bed then 'it' is not being used. But if 'it' is on deposit it must be being used.

Which means, or should mean (with a sane banking system) that entrepreneurs will have access to those funds to make more stuff.

Perhaps I should have said that demand, for all practical purposes, is infinite.

IB, I'd never heard of Say's Law before, but having skim read the Wiki article, it makes sense to me.

However, it applies to freely produceable and tradable goods and services. It does not apply to monopolies. I am all in favour of free markets, but you cannot have a free market in monopolies, by definition (you cannot produce more of a monopoly right or else it wouldn't be a monopoly in the first place), so slightly different rules apply.

(So don't go playing the 'Keynes was wrong therefore George was wrong' card, one has nothing to do with the other).

L, exactly. But actually you can't have money under the bed. If you have literally coins and notes under the bed, then that is just an interest free loan to the government. They have spent the money instead.

If you are daft enough to buy gold and hoard it, well fair enough, you have paid other people to mine and refine the stuff, they've been paid fair and square, it;s just that you haven't consumed the gold yet.

@Lola. As I understand it if the money is on deposit with a bank and the bank just chooses to accumulate excess reserves it doesn't get 'used' at least not until the bank changes its stance. Say's Law seems to depend on rational actors.

All markets clear, producers reinvest, banks lend out loanable funds.

Paul.

Quite. But banks thrive on the turn they make. So they cannot hoard it. Assuming that they are paying the depositor something, And even if they don't they have to cover their storage and accounting costs,

MW. Well, well. Something that has missed the MW noggin. Say's Law. Even I have known about it for yonks.

Lola, I was just pointing out that demand (for goods and services) is not infinite. There is some income where a person's demand saturates. They then lend money out not because they want the interest (like what poor people do) or to save for the future, but because they've literally run out of stuff to buy. Bill Gates being a prime example.

If you bear in mind that if everyone in some super-economy were to saturate their demand, it would probably be lower than the rich's spending today, since there's not much use to conspicuous extravagance if anyone can do it. Caviar? Yeah, how many kilos you want?

That's the only point I was making.

By the way, banks lend out a multiple of their capitalisation, they don't lend reserves. They do however have to settle debts in reserves, which is how a bank run can happen when Gordon Brown is in charge lolz.

So under the current system, if you put your money in the bank, they don't actually lend it. They pay off debts to other creditors (e.g. account holders who cash a cheque) with it.

"it would only be the price of homes in towns from which people emigrate which would fall - there would be the same number of homes but fewer households, so same supply, less demand."

I'm not sure that even this would be true. The evidence is that only a reduction in the ability of people to buy, i.e. either a restriction of credit, a rise in interest rates or a fall in real wages causes a reduction in house prices. The houses that are surplus to demand simply remain empty.

@ Bayard

There could well be fall in wages due to the effects de-agglomeration.

But, really, all things being equal, aggregate land rents stay the same.

You could, in theory lower aggregate HP's by building loadsa homes, but only at the expense of increasing deadweight costs.

It's a zillion times better to make housing more affordable, and at the same time eliminating deadweight costs(mis-allocation) by having a LVT.

(which of course you know)

But the spacial economists at the LSE, who appear to be the main cheerleaders for the "increase supply" solution, just don't want to even contemplate LVT.

Which is highly odd, IMO.

BJ, That's because it's the big property developers who are behind the "increase supply""solution" ultimately and dare I guess they are putting the odd quid the LSE's way?

I think Mark's nailed it with this: "But each and every plot of land is unique and a mini-monopoly in its own right. So each has its own value which cannot be influenced by the owner." Presumably, if you have an estate of 200 identical houses, then, within that estate, they are pretty interchangeable and you would probably find that, if they all came on the market at the same time and demand was low, then the price might have to go down a bit to get them sold, which is presumably one of the reasons why no-one builds large estates of identical houses any more.

Post a Comment